Children Separated at the Border Gain Help from Iranian Americans

It was 1988. She had just turned 5. The Mexican desert sun beat down on the crowded car as she sat on her mother’s lap in the front seat. The driver veered off the road despite everyone’s frantic protests and suddenly a herd of ATVs surrounded the vehicle. A helicopter hovered overhead as uniformed men pointed guns at the car from all directions.

“GET OUT OF THE VEHICLE WITH YOUR HANDS IN THE AIR.”

Ghoncheh, her mom, and the driver followed the guards’ directions. In the back seat, there was another family—a mom, a dad, and young boy close to Ghoncheh’s age. After they exited the car, one of the armed men opened the trunk to reveal two more people traveling with them, unbeknownst to the other occupants. As it turned out, the $25,000 that they paid to enter the U.S. through legal means was part of a scam that looked to deceive people like Ghoncheh and her mother who were desperately trying to follow the law.

Ghoncheh, who is now studying to get a Master’s in Public Policy from John Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), was born in Isfahan, Iran. Her mother was in a difficult marriage when Ghoncheh was born and filed for divorce, but the law in the Islamic Republic stated that Ghoncheh would only be able to live with her mother until age 7. Then she would have to be handed over to her father, whose family vowed never to let her mother see her again. In an effort to stay with her daughter, Ghoncheh’s mother packed their bags and they fled to Turkey in the dead of night. There, she applied for asylum in the United States, where Ghoncheh’s uncle was studying to get his PhD in Engineering. After their asylum applications were denied at consulates in Turkey, they tried in Spain. Then in Mexico. Everywhere they tried, they got denied.

Through the grapevine, they heard of a way to cross the border legally as long as they had the necessary documents and could afford to pay a substantial fee. Having already applied for asylum multiple times, they were prepared with the correct documentation, and Ghoncheh’s uncle scraped together all of his savings to cover the fee. That’s how they ended up in the car that day, being held at gunpoint by Border Patrol.

Once in the U.S., Ghoncheh and her mom applied for asylum—which they were eventually granted—but because they were conned into entering illegally, they were detained first. The Border Patrol separated the men from the women and children and took them to different detention facilities. Ghoncheh and her mom were sent to a facility with a giant grey room that had rows and rows of identical bunkbeds. The adults were dressed in neutral uniforms, but Ghoncheh and the other little boy were able to keep their street clothes on.

The guards played cartoons on the TV that wasn’t supposed to be turned on, allowed the mothers to sneak snacks into the sleeping area for the children, and even bought toys like bicycles for when it wasn’t too hot to play in the outside area. They made sure that the two children remained with their mothers the whole time—they even got to sleep in the same bed with them. While that initial border crossing was a terrifying experience, Ghoncheh felt safe and comfortable during her two-week detainment.

“Thinking about what’s happening now, I keep thinking this could’ve been me,” said Ghoncheh. “The whole point of my mom coming to the U.S. was to not be separated from me.”

In early May, the Trump Administration instituted a zero-tolerance immigration policy that calls for the prosecution of all who enter the U.S. illegally. Prior to this policy, illegally crossing the border was met with a misdemeanor and those involved could be subject to deportation, but criminal charges were unlikely and families were kept together while their cases were processed. Now, all persons crossing the border illegally are criminally prosecuted, regardless of whether they are seeking asylum (which is legal) or accompanied by minors.

The adults are immediately detained and placed in the custody of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The children are then placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services, specifically the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) which holds them in detention facilities and then transfers them to more child-friendly facilities until they can be united with a family member or a suitable sponsor inside the U.S. Typically, ORR deals with minors who cross the border alone, but now they are also tasked with caring for the children whose parents are still being detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“Once the parent and child are apart, they are on separate legal tracks,” said John Sandweg, acting director of ICE during the Obama Administration.

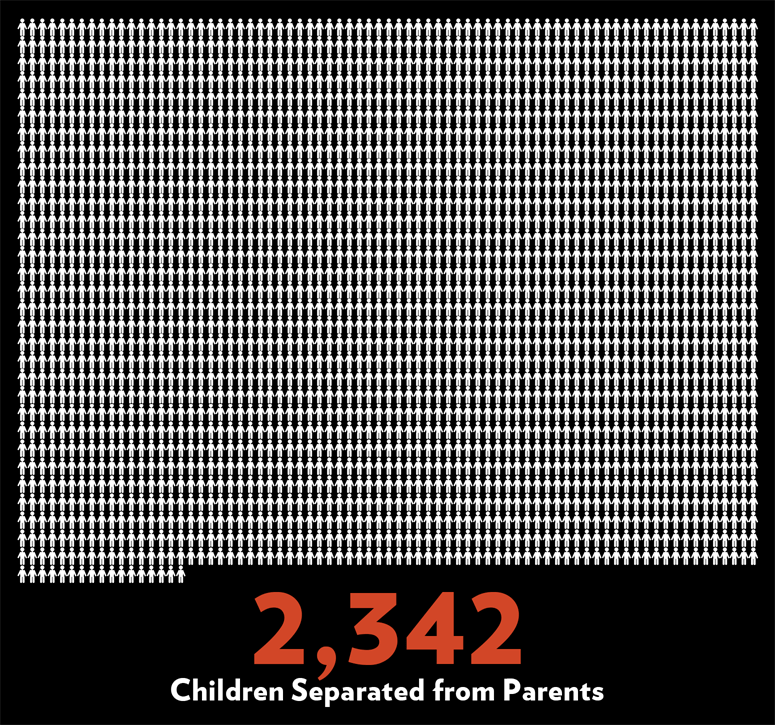

Since the policy’s implementation, at least 2,342 children have been separated from their parents according to the Trump Administration. Many have been shipped miles away from where they entered the border and been placed in makeshift shelters. These children have to go through deportation proceedings alone and often end up placed with ‘sponsors,’ other relatives who will claim them, or in other care facilities rather than deported.

“My 5-year old client can’t tell me what country she is from,” tweeted Laura Barrera, an immigration attorney aiding some of the children going through these deportation proceedings alone. “We prepare her case by drawing pictures with crayons of the gang members that would wait outside her school.”

Iranian Americans like Ghoncheh know what it’s like to leave the country they called home because of politics, religion, and terrible circumstances. Over one million Americans of Iranian descent live in the United States, and after the 1979 revolution, Los Angeles became home to the largest Iranian population living outside of Iran. Iranian Americans know how terrifying it is to leave everything behind and start over in a completely new land. That’s why, when news came out about children being separated from their parents at the Southern border, they decided to do their part.

With funding from an Iranian American entrepreneur and philanthropist, 10 immigration attorneys traveled to the Texas border to assess the situation, determine how best to help, begin assisting detainees on their legal cases, and take steps to reunite separated families. While the civil rights organizations working on the issue were receiving donations from around the country, this team was one of the first groups of lawyers to travel to the detainees and provide on-ground assistance. Iranian American Ali Rahnama, the legislative counsel for the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA), led the effort by finding colleagues who were able to take off work to join him at the border.

Two Iranian American lawyers joined by 8 other attorneys headed to the Texas border to help the separated children.

After wading through a torrential downpour, Rahnama and the other attorneys arrived at Port Isabel Detention Center (PIDC) where they began interviewing some of the 1,200 detainees. The lawyers tried to provide advice on how to tell their stories during their Credible Fear Interviews—the interviews they have to go through in order to be granted asylum—but it was hard because their minds were elsewhere.

“When we talked with the detainees, they couldn’t talk about themselves,” said Rahnama. “All they could think about was their children.”

Some had been there for more than a month without any contact with their kids. Many were told that they had to attend district court alone but would then be reunited with their children, only to come back from court and find that their children were gone. Others were forcefully pulled apart as soon as they stepped foot on U.S. soil. Neither the parents nor the kids knew what was happening when they were separated. A few of the lucky ones were able to contact a family member who had also been contacted by their child, and occasionally that led to finding the kid’s location—Michigan, Oklahoma, Washington state, anywhere but Texas. The really lucky ones were then able to facilitate a call between the detention facility where they were held and the location where their child was being held.

“Why did you leave me mommy?” one kid asked when finally being able to speak to his mom on the phone. “Don’t you love me?”

The stories of the detainees, when eventually told to the attorneys, were tragic. A medium-build man with a deformed face spoke of the violence in his home country that permanently disfigured him. A lady in her late twenties admitted that her daughter’s cries echoed in her mind every night before she fell asleep. A couple explained that their children were harassed on the way to the U.S. and wouldn’t let go of their parents until they were forcibly separated by ICE. Many of the women in the facility had experienced so much rape in their lives that they didn’t even think of rape as abnormal. One woman even said she was raped in front of her daughter on their journey to the border.

The lawyers all knew that the parents had very legitimate reasons for seeking asylum, but they’d have to prove that in their Credible Fear Interviews in order to be granted asylum and reunited with their children. If the interview failed to convince the officers at the US Citizenship & Immigration Services of the immigrant’s need for asylum, they would have the right to appeal that decision to an immigration judge. However, other than the few lawyers who offered to educate the detainees pro bono, the immigrants were not provided with any legal counsel nor informed about the asylum-seeking process. As a result, asylum seekers are being denied en masse. Many were offered a chance to be reunited with their children if they signed deportation papers, but those who signed the papers were often deported without their children. Sandweg says that in such cases, “there is a very high risk that parents and children will be permanently separated.”

“The problem is that ICE is trying to trick them at every turn,” said Rahnama. “At every point of this process, they are being intentionally targeted.”

In response to the backlash the child separation policy received, President Trump signed an executive order stating that families should be reunited and detained together indefinitely, but that’s easier said than done. While ORR does have a database of the children they’re holding, ICE does not seem to have one of the parents—or at least they’re not sharing it with immigration attorneys and civil rights groups on the ground. As a result, figuring out how to match parents with kids has become an even more daunting task, requiring DNA tests. So far, only four children have been released into the custody of a parent in the U.S., but only one of the four was reunited with the parent that originally brought them to the U.S.

“A lot of these people just want better opportunities for their kids. It was the same situation with my mom,” said Ghoncheh. “She did not want to leave her family behind; she didn’t want to leave her life. She didn’t see her family for 15 years and it pained her. To this day, it scarred her. But she did all that just to give me a better life.”

Ghoncheh in 2018

And Ghoncheh does have a better life. She went to undergrad at the University of Illinois at Chicago and obtained a degree in electrical engineering which landed her a job at Proctor & Gamble. After 5 years with the company, she left the private sector and went to Kenya to work in development. While there, she helped with the founding of R.O.C.K., a non-profit organization that provides academic assistance and peer support to at-risk youth in Kenya. Now, she’s back in the States getting her Masters at SAIS and volunteering in her community during her free time. While Iranian Americans are one of the most successful immigrant groups, immigrants in general contribute greatly to the societies they join, including the United States.

Unfortunately, the zero-tolerance policy isn’t the only policy to come out of the Trump Administration that targets immigrants. The President also signed an executive order that bans individuals from 7 countries from coming to the United States. That list includes Iran, Ghoncheh’s homeland and the country with one of the most pro-U.S. populations in the Middle East. Policies like this prevent incredible entrepreneurs, innovators, engineers, philanthropists, and doctors from contributing to the economic and social fabric of the United States while also sending a negative message to the people and countries being turned away. President Trump and Congress have the ability to end harmful immigration policies like these ones, but so far they have not taken definitive action.

“Chances are that the kids we’re locking up are going to be the next inventors, the next scientists, the next people to find cures to diseases… and we’re not giving them that chance,” said Ghoncheh. “I was very lucky that I was given that chance, and I hope that we can look at my story and see the person that I am and [realize] those children are not any different.”

UPDATE: As of June 12th, a total of 57 children have been released from government’s custody, meaning at least 2,285 children remain separated from their families.